How do healthcare providers diagnose Parkinson's Disease?

To date, there is no single test that can accurately identify the presence of Parkinson’s disease. Instead, the diagnostic procedure involves assessing medical history, presenting symptoms, neurological tests, and a physical examination that a healthcare professional conducts.

Although Parkinson’s disease is often diagnosed when the classic motor (movement) signs or symptoms are present such as tremors, muscle rigidity, balance issues, festinating gait, or difficulty moving, current research points to the identification of non-motor signs. More specifically, signs such as the loss of smell, dizziness, constipation, sleep disturbances, and depression often become evident ahead of the motor-related signs and can potentially be used for earlier diagnosis of the disease in the future.

If a healthcare professional suspects Parkinson’s disease, the next step is a referral to a doctor who specializes in neurological disorders, such as a neurologist.

Examinations

A combination of physical, neurological, and imaging examinations may be necessary to rule out the possibility of other neurological diseases that may cause symptoms similar to Parkinson’s disease. The physical exam includes a visual assessment, palpation (feeling limbs and muscles), percussion (tapping body parts to produce sound), and auscultation (using a stethoscope). During a neurological exam, an individual may be asked to walk, sit, stand, and move the limbs in specific ways to evaluate coordination and balance. Memory, sensory function, and reflexes may also be assessed.

In addition, imaging tests such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET) scan, or an ultrasound may be performed. A specialized single-photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) scan called a dopamine transporter scan (DaTscan) is an alternative imaging exam, but it is expensive and not performed routinely.

The final diagnosis depends on the cumulation of results from the series of tests that are conducted.

Medication

There are many drugs that are being used to treat the PD physiological disease process as well as many drugs that are used to treat the symptoms that the disease brings with it. Unfortunately, no drug is currently available that reverses the effects of Parkinson’s or stops the disease from progressing.

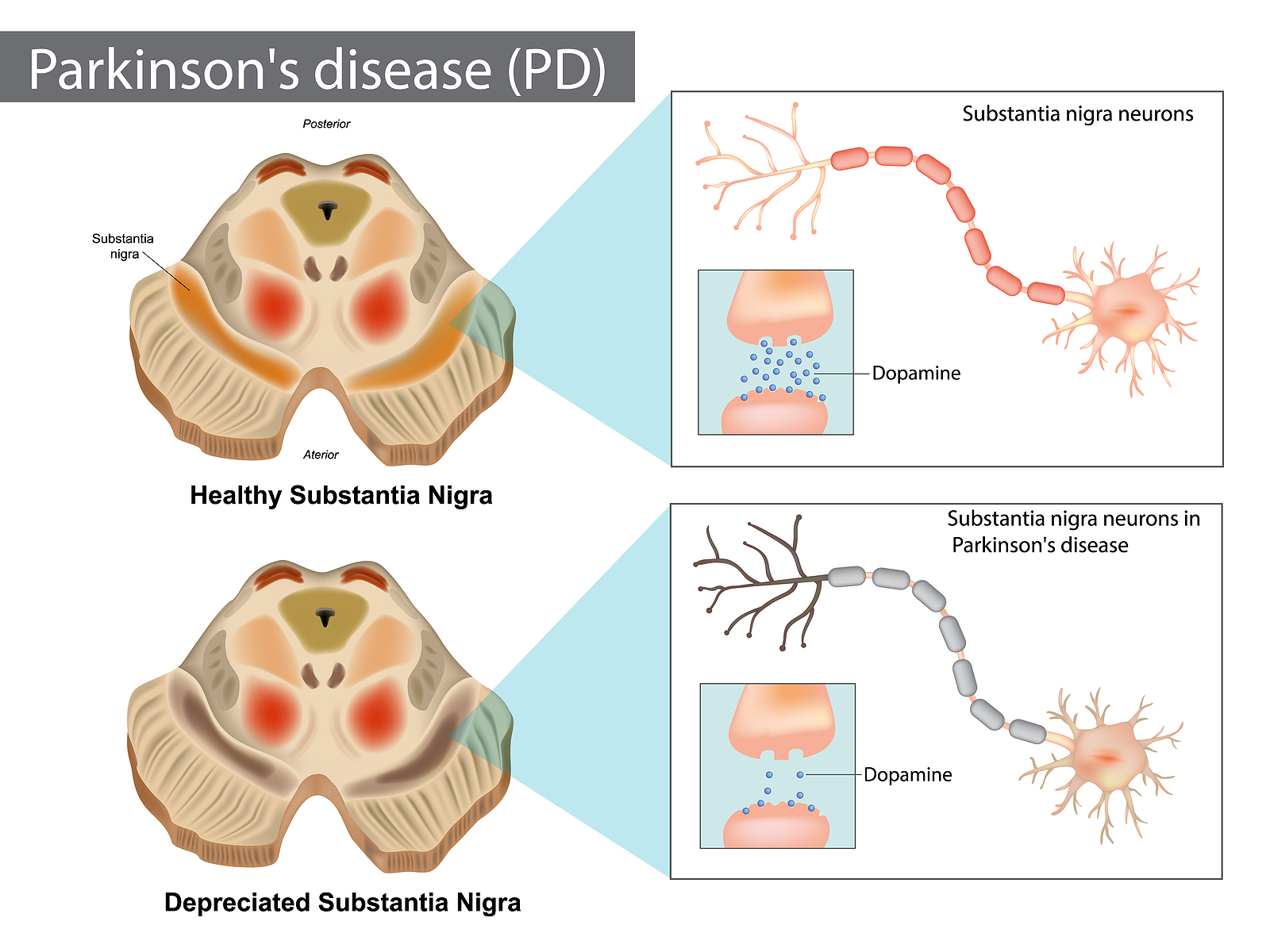

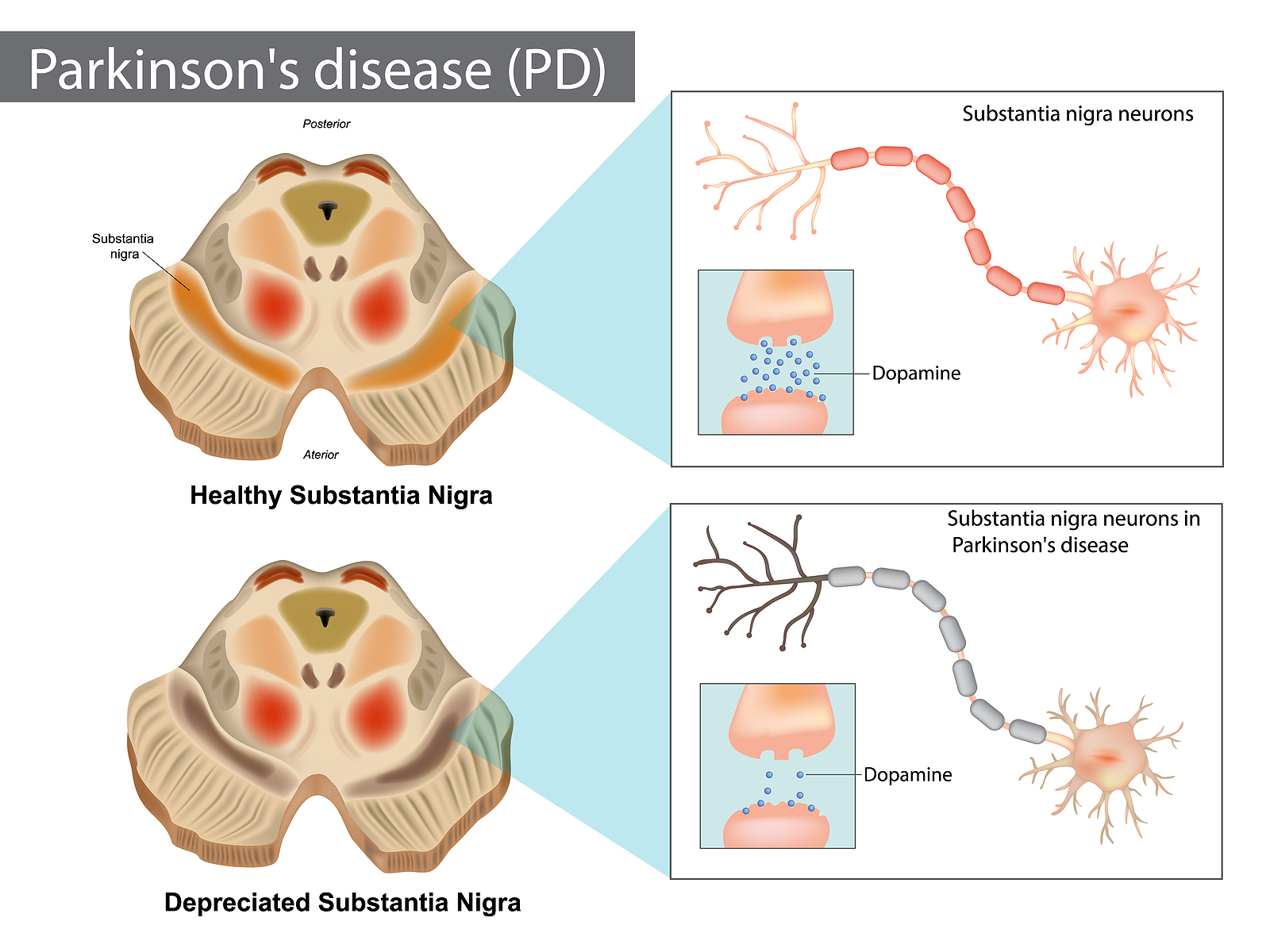

Initial drug treatment typically aims to restore and mimic the effects of dopamine, or to stop the breakdown of dopamine in the brain. Some doctors often recommend a trial period of a dopamine-type medication such as levodopa to see if it is effective at decreasing symptoms (e.g., tremors, motor difficulties). Levodopa, which is an amino acid the body converts into dopamine, became the primary agent to treat the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease during the early 1900s.

Furthermore, a positive response to levodopa was an indication or confirmation of Parkinson’s disease, and due to its effectiveness it was once considered the gold standard for Parkinson’s management. In some cases, levodopa is still the first line of treatment due to its function as a dopamine replacement agent.

However, levodopa requires 2-3 weeks to initially take effect, and it has a short half-life of about 90 minutes, which means the body rapidly breaks it down. As the medication’s effects wear off, the symptoms may start up again until another dose of levodopa is taken. In addition, levodopa may cause dyskinesia (uncontrollable fidgeting) as the levels of dopamine start to increase in response to taking this drug, especially in individuals with young-onset Parkinson’s disease. This drug also loses its effectiveness over time.

To combat these types of issues, levodopa may also be combined with another medication called carbidopa to form Sinemet (carbidopa-levodopa), which helps the drug cross into the brain. The combination of these two drugs also offers extended-time release that improves its effectiveness.

As a result, Sinemet is now referred to as the gold standard in Parkinson’s treatment in comparison to other drugs that mimic dopamine in the brain (dopamine-agonists) or those that stop the breakdown of dopamine, such as monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitors, catechol-O-methyl transferase (COMT) inhibitors, and anticholinergics.

A doctor will evaluate the most up-to-date and effective medications for each individual case. The medication that is recommended also depends on the presenting symptoms, an individual’s age, overall physical health, lifestyle, and whether the symptoms affect activities of daily living such as maintaining balance, walking, and using the hands properly.

Unfortunately, some of the medications that are used to treat Parkinson’s disease can cause or worsen certain symptoms (e.g., dyskinesia) as the dosage is increased. It is important to note that dyskinesia is not a symptom of Parkinson’s, but rather a side effect that is caused by some medications. Many patients choose to continue taking medication despite the occurrence of dyskinesia because without the medication their other symptoms worsen, making it difficult to manage their daily lives.